The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy has it all. As the brainchild of the brilliant Douglas Adams—lost to us much too early at the age of 49—what began as a humble BBC radio show has since morphed into a multimedia pop-culture phenomenon.

It’s a simple tale really—the galactic adventures of the last surviving man after the destruction of Earth, made possible by his rescue courtesy a human-like alien who happens to be a writer for the travel guide for which the entire franchise is named.

Equal parts science fiction and satire (some would argue for a greater percentage of the latter), the first novel of the series is everything you would want it to be—hilarious, insightful, and prescient. Here are a couple reasons why—several decades later—we’re still talking about it.

The Lines

Even without reading the book, anyone can appreciate the classic lines Adams sprinkled throughout the text:

Most of the people living on [Earth] were unhappy for pretty much of the time. Many solutions were suggested for this problem, but most of these were largely concerned with the movements of small green pieces of paper, which is odd because on the whole it wasn’t the small green pieces of paper that were unhappy.

Mr L Prosser was, as they say, only human. In other words, he was a carbon-based bipedal life form descended from an ape. More specifically he was forty, fat and shabby, and worked for the local council.

On Earth it is never possible to be further than sixteen thousand miles from your birthplace, which really isn’t very far…

…what nature refused to do for them they simply did without until such time as they were able to rectify the grosser anatomical inconveniences with surgery.

They have attempted to acquire learning, they have attempted to acquire style and social grace, but in most respects the modern Vogon is little different from his primitive forebears.

…[he] decided he quite liked human beings after all, but he always remained desperately worried about the terrible number of things they didn’t know about.

Or do you just find that coming to terms with the mindless tedium of it all presents an interesting challenge?

You just won’t believe how vastly hugely mindbogglingly big [space] is. I mean you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.

The whole Poghril tribe had died out from famine except for one last man who died of cholesterol poisoning some weeks later.

…the main reason why he had had such a wild and successful life was that he never really understood the significance of anything he did.

He attacked everything in life with a mixture of extraordinary genius and naïve incompetence and it was often difficult to tell which was which.

Many men of course became extremely rich, but this was perfectly natural and nothing to be ashamed of because no one was really poor—at least no one worth speaking of.

Isn’t it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?

…an Antarean parakeet gland stuck on a small stick is a revolting but much-sought-after cocktail delicacy and very large sums of money are often paid for them by very rich idiots who want to impress other very rich idiots…

It must be something very important because there certainly seems to be a hell of a lot of it.

There are of course many problems connected with life, of which some of the most popular are: Why are people born? Why do they die? Why do they want to spend so much of the intervening time wearing digital watches?

So long as you can keep disagreeing with each other violently enough and slagging each other off in the popular press, and so long as you have clever agents, you can keep yourselves on the gravy train for life. How does that sound?

Science has achieved some wonderful things, of course, but I’d far rather be happy than right any day.

It is of course well known that careless talk costs lives, but the full scale of the problem is not always appreciated.

Unless handled with tranquillity this equation can result in considerable stress, ulcers and even death.

The Influence

It’s hard to overstate the reach of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Asteroids owe their names to it. The same with certain fish species. Numerous video games are based on it. And millions—including many you know well—have been inspired by it. Take a look.

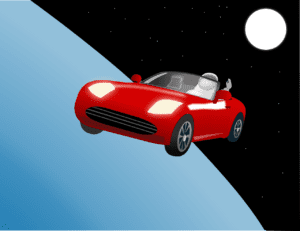

Elon Musk

Musk has praised the Hitchhiker’s Guide for having a significant impact on his life, even placing a copy in the glovebox of the Tesla Roadster that his company SpaceX launched into orbit around the sun.

Radiohead

The British band’s iconic third album, OK Computer, takes its name from the way in which the president of the galaxy addresses his own computer. And one of the album’s best tracks—”Paranoid Android”—is named after the robot Marvin the Paranoid Android.

Coldplay

Not to be outdone by their contemporaries, another British band gave a shout out to the Hitchhiker’s Guide with their track “Don’t Panic,” referencing the helpful phrase found on the cover of the guide itself.

And their song “42” may or may not be a reference to the absurdly simple number given by the computer Deep Thought as the answer to the Ultimate question of Life, the Universe, and Everything.

The bottom line: Snag a copy of this thing—you can’t go wrong.