It was 1995, and I honestly had no idea how the government segregated America.

I was just 17, more concerned with matters surrounding the cafeteria menu—and late-night eats.

Having landed in college in St. Louis, Missouri, it all seemed rather familiar anyway. Sure, I had grown up near New Haven, Connecticut, but things looked about the same.

There was poverty in the middle, ringed by various degrees of wealth on the periphery. The center, of course, was dark, and the surroundings more pale.

Such was the world I was born into.

I remember hearing the words of Bruce Hornsby echoing in my head: That’s just the way it is.

Granted, despite some shading to my skin, I lived on the perimeter, meaning I had the luxury of shrugging my shoulders.

But despite having been handed a few things, that wasn’t enough to quell my natural curiosity.

How was it that St. Louis looked the same as New Haven, which looked like Chicago, which in turn reminded me of the Bay Area?

Couldn’t even one city, somewhere on this massive piece of land, come up with a different formula?

***

Twenty-two years later, I learned why the answer to my question was a resounding no: Because, as above, the government segregated America.

In a country that prides itself on decentralization and states’ rights, it was a heavy-handed federal government that engineered—and ultimately wrecked—our cities.

In other words, the blatant and destructive segregation was not a de facto phenomenon, guided by personal instinct and private enterprise.

What I had observed—by that point the status quo—was a de jure creation, the result of government policy, also known as the law.

Common sense will tell you that for geographically and legislatively disparate regions to resemble each other, a strong centralized authority has to be pulling strings.

But you don’t have to take my word for it.

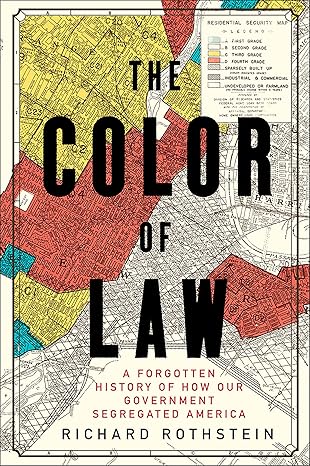

Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, is a far more trustworthy source, one who offered so many references in his 2017 work that any counterargument could only be that of an apologist—or racist.

What exactly did Rothstein, a leading authority on housing policy, point out?

A lot.

To start, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal instituted the nation’s first public housing for civilians not involved in defense work. These housing developments were strictly segregated by race, even in places where there was no preexisting pattern of segregation. There were whites-only and blacks-only projects, and in the less common case of “mixed” projects, blacks were limited to designated areas.

Around the same time (the Great Depression), the Roosevelt administration created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to purchase existing mortgages at risk of foreclosure and reissue them with more favorable terms. The HOLC designed color-coded maps, labeling predominantly black neighborhoods as red, thus assuming they were high-risk and not good candidates for the program. Such home owners eventually became renters.

Similarly, the newly formed Federal Housing Administration (FHA) began to insure bank-issued mortgages to encourage continued lending. The only catch was a whites-only requirement, meaning lending policies began to reinforce racially homogeneous neighborhoods.

The same FHA also provided loan guarantees to developers building massive suburban housing projects—provided that the developments were restricted to white families. Furthermore, the FHA encouraged the use of restrictive covenants that prohibited suburban homeowners from selling their properties to black families.

All of the above was fortified by state and local policies that were far more likely to zone for industrial entities in black neighborhoods and/or simply displace those neighborhoods via highway construction. Concurrently, multifamily units were discouraged in white neighborhoods to prevent displaced residents from relocating there.

Mercifully, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 put an end to the injustice, but the damage—many decades in the making—had clearly been done.

***

It’s now 2025, and some things never change.

Well, the name of my home—Rochester, New York—is different.

But I still live on the rim, shielded from history.

I’ve watched as proposals for affordable housing in my cozy suburb have been met with death threats.

And like a good American, I continue to shrug my shoulders.

Yes, instead of Bruce Hornsby, I now hear Tupac.

And every January, I hear the voice of Martin Luther King, Jr.

I always take a moment to lament the regrettable parts of our collective story.

And just as I did three decades ago in St. Louis, I wonder what’s for dinner.

2 Responses

Most of human kinds problem are human made, like the current climate issue.

Absolutely. All the conflict zones throughout the world have resulted from flawed decisions, borders, and premises—in other words, humans being humans.